On 23rd November 2021, the Ministers responsible for East African Community (EAC) Affairs recommended to Member State Leaders the entry of the DRC into the economic block. Our commentary sets out some background on this vast country and what opportunities lie in store for investors.

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (DRC)

On 23rd November 2021, the Ministers responsible for East African Community (EAC) Affairs recommended to Member State Leaders the entry of the DRC into the economic block. This followed a verification exercise carried out on the country. The EAC Secretary-General, Dr Peter Mathuki said: “By DRC joining, the Community will open the corridor from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean, as well as North to South, hence expanding the economic potential of the region”. The negotiation phase between the DRC and EAC commenced in January 2022. The intention is to admit the country into the block by the end of the first quarter of this year. On admission, the DRC will become the seventh Member State of the East African Community.

The commentary in this issue of the newsletter sets out some background on this vast country. What follows has been extracted from a variety of publications including the online version of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, the IMF and the World Bank, among other sources.

Background

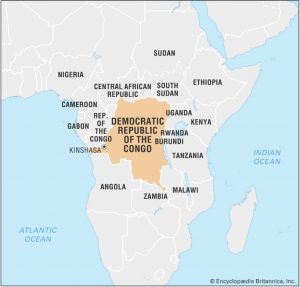

The DRC is the second largest country on the African Continent and the largest in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is situated in Central Africa but largely landlocked save for a 40 kilometre coast line on the Atlantic. Its land mass is as large as Western Europe. The capital city is Kinshasa, which is the largest city in the Central African region.

Source: Britannica

The country is home to more than 200 ethnic groups who settled there between the 10th and 14th centuries. Similarly, there are over 200 languages spoken in the DRC with Swahili, Tshiluba, Lingala and Kongo being the national ones. However, given its colonial past, the official language is French. Half of the population are Roman Catholic and around 20% follow traditional beliefs. Over half of the population, currently estimated at nearly 94 million (World Population Review), live in the rural areas of the country. The DRC population growth – 3.19% – is reportedly one of the highest in Africa. 46% of the population is under the age of 15. According to the World Bank, almost three quarters of the country’s population live below the poverty line, and they account for one sixth of the those living in extreme poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa. Life expectancy is well below global averages because of poor medical care.

Until 2006, DRC had a turbulent past with civil wars plaguing the country. In December 2005, the country conducted a referendum to adopt a new Constitution which was supported by 84% of the population (WorldAtlas). The Constitution “decentralised authority” and created provinces largely on “cultural and ethnic lines”. There are three levels of Government comprising the Executive, Judiciary and Legislature – a model that has or is being adopted by most countries in the region. The President appoints a Prime Minister from the majority party in Parliament and the two appoint the country’s Cabinet. The legislature is made up of the National Assembly and the Senate. The Judiciary is, under the Constitution, granted independence but in practice this has not necessarily worked.

History

As far back as the 15th century, the country developed several “state systems” ruled by a monarch with relatively well-defined political institutions. The slave trade became prevalent and powerful individuals in the outlying areas in the rain forest eroded the King’s powers resulting in incursions from other parts of the region. Society centred around village units and “corporate groups of related and unrelated people”.

The infighting during that period made the country a relatively easy conquest for King Leopold II of Belgium, who effectively started trade with Europe. With the help of British explorer, Henry Morton Stanley, treaties were signed with some 450 independent rulers leading to Belgium controlling the area. The Berlin West Africa Conference in the late 1800s allowed Belgium to colonise the area which became known as the Congo Free State. The intention at the time was a “humanitarian mission of ending slavery and bringing religion and the benefits of modern life” to the local population.

Stanley had previously said that without a railway “the Congo was not worth a penny”. In order to ensure that European companies could profit in their ventures in the area, a railroad was built using coerced and indentured labour. There was a general outcry globally of the conditions imposed and in 1908 the Belgium Parliament voted to purchase the land in the Congo Free State from the King. The atrocities, however, meant that ruling the area was no simple task.

While Belgian rule put a stop to some of the atrocities, there was no attempt made at political reforms and the local population continued to be second class citizens. As in many colonised countries in Africa, political development was not allowed for the local population bringing many issues. It wasn’t until 1957 that the indigenous population were allowed to experience some form of democracy through the reform of local Government. A political manifesto drafted by a Belgian professor, A A J van Bilsen, entitled “Thirty-year Plan for the Political Emancipation of Belgian Africa” in 1956, began the political rise of the Congolese people. The Alliance des Bakongo led by Joseph Kasavubu called for immediate independence resulting in pro-independence sentiment across the country. Key among them was the Congolese National Movement which, in 1958, led by Patrice Lumumba started a period of militancy. The colonial power found it more difficult to rule as unrest spread and in January 1960, Belgium held a conference with the nationalist organisations to agree on how to transfer power. Independence was finally granted on 30th June 1960 but with it came the “Congo Crisis” with the army mutinying. Belgian troops were dispatched, at least on the face of it, to protect their citizens. Following national elections, and as a compromise, Joseph Kasavubu became President and Patrice Lumumba Prime Minister. Despite this compromise, the two men were at loggerheads with each other and in reality, neither was in control.

Adding to the confusion was the Katanga region declaring independence under Moise Tshombe with support from Belgium. The President and Prime Minister sought intervention by the United Nations which added to the tension. Mr Lumumba asked the Soviet Union for assistance bringing the Congo into the Cold War. As the country broke up into four areas, the army, under Joseph Mobutu, took power with a caretaker Government. Patrice Lumumba, now on the run, was captured in December 1960 and executed by the Katanga Government. The secession was finally brought under control in January 1963 although pro-Lumumba supporters tried again in September 1964, but this too failed the following year. A civilian Government under Cyrille Adoula began in August 1961 but was unable to effectively deal with the secession threat and was replaced by Tshombe in July 1964.

The Army Chief of Staff, Joseph Mobutu (later to become Mobutu Sese Seko), carried out another coup in November 1965 and became the President. He renamed the country Zaire in 1971 as a means of returning to the cultural heritage. He faced two invasions from the Congolese National Liberation Front operating out of Angola that were quelled in the first case with help from Morocco and the in the second France. Mobutu also embarked on a nationalisation programme ousting foreign owned companies which resulted in a collapsed economy. Between 1970 and 1990, the country was a single party state controlled by him. He did accept multi-party politics in 1990 which coincided with the end of the Cold War but with allegations of widespread embezzlement of Government coffers, many of his Western supporters cut aid and ties with the country. He relinquished power in 1991 when Etienne Tshisekedi became Prime Minister. However, Mobutu stayed in the background playing one group off against the other and allowing the army to loot and plunder, resulting in the end of Tshisekedi’s rule and bringing in Kengo wa Dondo as Prime Minister supported by Mobutu, who was still President, in 1994.

The Rwandan genocide allowed Mobutu to come back into favour with the West by offering France and Belgium support in their backing of Rwanda’s Hutu Government. He also supported the Hutu exiles in the country and encouraged attacks on Tutsis. This led to Rwanda teaming up with Laurent Kabila who led an alliance to liberate the country from Mobutu. Kabila also received support from Angola and Uganda. While Mobutu was seeking medical treatment in October 1996 outside the country, Kabila launched an operation to take control entering Kinshasa in May 1997. While Mobutu did return from his treatment, he fled shortly thereafter into exile where he died.

Kabila took over the Presidency and renamed the country the Democratic Republic of Congo. With the help of foreign aid, he was able to bring some stability to the economy but did not seem inclined to move towards democracy with the banning of political parties and demonstrations. The result was a rebellion by his earlier supporters in the eastern part of the country and five years of civil war. The 1999 Lusaka Peace Accord and use of UN forces brought about a ceasefire, although pockets of fighting continued. In January 2001, Kabila was killed, and his son Joseph ascended to power. It wasn’t until April 2003 that the civil war ended with a Transitional Government and Constitution in place.

The civil war left the new Government with a country that was barely functioning with no infrastructure and an economy in tatters. The President, with foreign aid, worked on rebuilding but certain areas of the country were inaccessible due to continued fighting. A new Constitution came into place in 2006 and Joseph Kabila won the Presidential election that year. Despite this, fighting continued.

Further elections were held in November 2011 with Kabila and Tshisekedi vying for the Presidency which was eventually won by Kabila but with 100 parties holding seats in Parliament. The next election, due in 2016, did not take place till 2018, although not in all parts of the country, and there were concerns that Kabila would seek to extend his term unconstitutionally. Kabila in the meanwhile, confirmed that he would not stand for re-election. The election was eventually won by Felix Tshisekedi (son of Etienne who died in 2017).

Economy

The DRC economy pre-independence was largely driven by the extractive industry under the control of foreign companies, in particular Belgian. The Mobutu regime nationalised the industry which was plagued with embezzlement particularly by Mobutu and his cronies. While most global institutions and allied countries turned a blind eye to what was happening, the collapse in copper prices in the seventies resulted in audits of the state enterprises revealing the extent of the grab. Nevertheless, as a Cold War ally, Zaire, as it was then known, continued to be supported which kept the economy going, with them only seeking reforms after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc.

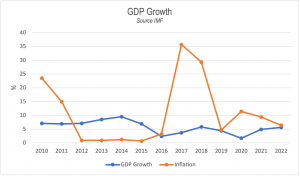

In the early to mid-nineties, the country experienced negative growth of 8.5%, which only turned positive in 2002, and whilst in 1994, inflation peaked at 23,770%! Per capita incomes at the time became one of the lowest in the world and a substantial informal sector emerged. It wasn’t until 2001 that the country moved to a more market-based economy with help from the IMF and the World Bank and a raft of structural reforms implemented.

Like most parts of the Eastern Africa region, the agriculture sector contributes 20% to the DRC’s GDP and subsistence farming accounts for 75% of the employment. Unfortunately, a deterioration of the infrastructure to support this important part of the economy, has led to a reduction since independence and a shift towards imports. Coffee is the main export from the DRC, but a considerable amount of the production is smuggled out of the country. Palm oil, rubber and cotton which were a significant part of this sector are now negligible.

Mineral deposits have become a major resource for the country accounting for almost 90% of its exports. According to Britannica, the major area of the country rich in minerals is Katanga, although there remain instances of fighting here, and includes “copper, cobalt, zinc, cassiterite (the chief source of metallic tin), manganese, coal, silver, cadmium, germanium (a brittle element used as a semiconductor), gold, palladium (a metallic element used as a catalyst and in alloys), uranium, and platinum”. Other parts of the country similarly have abundant natural resources. The country has significant hydroelectric resources estimated to “make up one eighth of global capacity and perhaps half of Africa’s potential capacity”. The capacity is widely used in the resource heavy areas of the country and the capital.

Manufacturing plays a small role in the economy plagued, ironically, by erratic electricity and difficulty in importing machinery.

The banking sector is well developed but despite this, the unbanked represent a significant proportion of the economy due to the large informal sector.

Outlook

Years of neglect and plundering has left the DRC’s economy in tatters but there are clear signs of the full potential coming through. The lack of infrastructure is a major obstacle for the country and considerable improvement will be required to pull the DRC out of the poverty trap. Politically the country is relatively stable now.

Meanwhile, the DRC joining the EAC will result in a market of almost 250 million people and in the long run, this will be a good thing for Eastern Africa.