This is a commentary and comments are welcome on email to info@eaa.co.ke

WHAT TO EXPECT IN 2023

Introduction – a look back at 2022

After a tumultuous 2 years of Covid-19 in 2020 and 2021, the world began showing a sense of optimism in the early part of 2022. Most countries were seeing economic growth – albeit from a significantly depressed base – and with the belief that Covid was largely behind us, there was considerable relief.

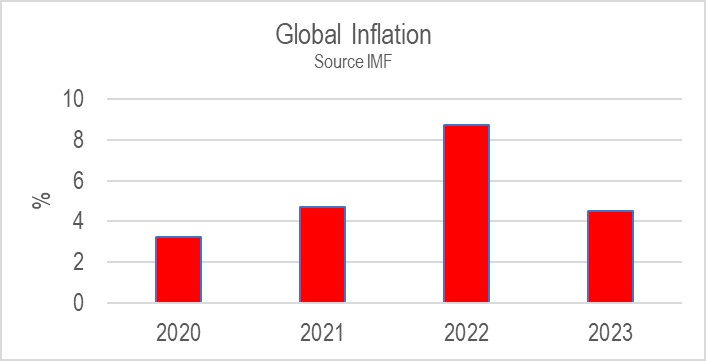

Unfortunately, in February 2022 the Russia-Ukraine crisis started and what was expected to end in a matter of weeks, persisted throughout the year and continues into 2023. With the crisis came a possible economic downturn and a period of high inflation globally. The impact of the conflict in Europe was, and continues to be felt, in most parts of the world with high oil prices and a shortage of wheat, maize and fertiliser which Russia and Ukraine are the primary suppliers.

In the Eastern Africa region, hostilities in Ethiopia appears to have died down following the peace talks. However, the DRC issue with the M23 rebels is ongoing despite the efforts of a peace mission led by the former President of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta. South Sudan too was, and continues to be in state of disarray with little progress made in 2022 on the Peace Accord.

So, what does 2023 have in store?

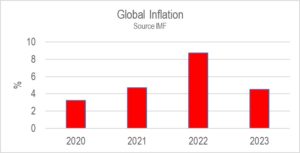

The Economist in their publication “The World Ahead 2023” cite three shocks that created turmoil in 2022 which they expect will continue to do so in 2023: geopolitical; energy and commodities; and macroeconomic stability. Perhaps, there is a fourth in Covid-19, which despite the feeling that it had disappeared, has surged through the Chinese population after the lifting of three years of tough restrictions, leading to concerns of a new variants again spreading from China. Clearly the world is not over the pandemic although the populace seems to have other ideas after two years of lockdowns and economic downturn. That said, the numbers are not as severe as the world saw in the past, but interestingly those parts of the world that adopted a “Zero-Covid policy” saw a significant spike in numbers in late 2022 going into 2023 (see chart). This was particularly true in Oceania and China but it is possible that the peak has passed and numbers of infections are falling. However, complacency will need to be avoided as Covid-19 has not disappeared. Africa did not experience a significant spike in late 2022 early 2023.

In addition, climate change and global warming will also play a big role in shaping 2023.

Geopolitics

|

“The American-led post-war world order is being challenged, most obviously by Mr Putin, and most profoundly by the persistently worsening relationship between America and Xi Jinping’s China”. Economist The World Ahead 2023 |

According to the Economist, the biggest shock that we will see in 2023 is geopolitics. While America and much of the West have rallied against Russia in the conflict, there is no sign that NATO will be directly involved, instead propping up Ukraine with arms and other aid. More importantly, perhaps, much of the developing world does not appear to be in full support of sanctions against Russia and are generally ignoring the call. Indeed, China and India would seem to be actively supporting Russia, perhaps not in the armed conflict, but certainly economically. The upshot of the conflict, however, is global uncertainty and instability.

Many African countries voted against sanctions which is not surprising given their need for products that they import from both Russia and Ukraine, which have been severely impacted both by the war and the sanctions. The risk of the current conflict escalating to a nuclear one is heightened and this is perhaps the biggest risk the world faces in 2023. With some luck and a prevailing wind, the Russia-Ukraine situation will calm down in 2023, although this is by no means assured.

China clearly opposes “the values upon which the Western order is based” according to the Economist and this is a fact that is clearly seen by all and sundry. From a geopolitical perspective, China is flexing its muscles and its long-held designs on Taiwan are in some ways much less in check. The Chinese leadership do not really care what the West’s view on this is and will continue to seek the “return of Taiwan”, although clearly the US position including the “strategic ambiguity” on whether it would intervene militarily in any Chinese attempt to take the island by force, does remain a deterrent. Another potential flashpoint is the increased militarisation of the China – India frontier over a long simmering border dispute, which will also add to the global geopolitical risk.

China does, however, have its own problems with Covid-19 raising its ugly head, a real estate industry in turmoil and an economy which is growing at its slowest pace in decades. Its people have already made their views clear on the country’s zero Covid policy and could well rise against other policies in the country, which will likely keep Mr Xi Jinping and his Government on their toes.

Iran is another geopolitical risk in 2023. The country has been facing street protests through much of 2022 (which started in 2021 for a variety of reasons) from its citizens following the death of a 22year old girl who was in custody of the country’s morality police. While the Government claimed her death was a result of underlying health conditions, her family, and indeed the United Nations, have said she died from “alleged torture and ill-treatment”. The security forces, as evidenced by videos that have been circulated on social media, have dealt with the protestors with extreme brutality resulting in more people coming onto the streets. The Iranian football team, at the recently held World Cup, refused to sing the National Anthem and expressed their solidarity with the protestors. Could 2023 be a turning point for the Iranian regime in a manner similar to their toppling of the Shah of Iran in 1979? Suffice to say, Iran is a conundrum that many do not, and perhaps will not ever, understand nonetheless the citizens are rising more and more often.

Closer to home, the geopolitics of Ethiopia, DRC, South Sudan and Somalia are likely to continue to make headlines this year.

Energy and commodities

Not since the early nineteen seventies has the world seen an energy crisis in the same vein as it is currently facing. The Russia-Ukraine conflict has seen a significant increase in oil prices (although now showing signs of abating) and over reliance by many countries on Russia has proved difficult. Despite sanctions, many Western countries continue to rely on Russian gas and the need for alternative sources, both of fossil fuels and renewables, has become a priority.

Some European countries have even turned back to the dreaded coal as a means to fill the deficit. In 2022, the world saw an unnaturally high number of climate related disasters partially brought on by the use of fossil fuels, and, the Russia-Ukraine crisis has brought this reliance to the forefront again but for different reasons. As Europe faces its winter, which seems to be quite cold, Governments are struggling to keep their citizens warm. With no end in sight to the conflict, this is a trend that will almost certainly go on in 2023. The priority, therefore, for most countries will be the ability to supply affordable energy but not necessarily the most environmentally favourable.

Perhaps, as winter in the Northern Hemisphere passes, the focus may once again shift to renewables and sources other than Russia for energy needs.

Russia and Ukraine have long been a major exporter of grains and fertilisers, both of which are critical to many parts of the world, and in particular Africa. According to The Economist, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda receive 40% of their wheat from these two countries. Rising commodity prices and scarcity has become the order of the day.

The World Food Programme has estimated that between 2011 and the end of 2022, the number of people facing food insecurity has risen from 282 million to 345 million. This number is expected to increase in 2023 as the Russia-Ukraine conflict continues, many parts of the world face adverse climatic conditions whilst conflict in other areas remains. The consequences of a severe basic food shortage are too horrible to imagine.

The Economic Intelligence Unit in their report Commodities Outlook 2023 expect “most commodity prices, especially softs, to recede in 2023 in the face of slowing demand globally, but an only limited increase in supply means that prices will remain high in level terms”. Climate change is likely to “remain the big wild card in 2023” which may impact global commodity prices. They further expect that supply chain disruptions that emanated from the pandemic will reduce in 2023, but again, this is largely dependent on the outcome of China lifting its zero Covid policy which has seen, and may continue to see a spike in infections. Food commodity prices will largely be dependent on the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Oil prices are expected to average more than USD 85 per barrel. The US Energy Information Agency has forecast average prices in 2023 at USD 83.1 falling further in 2024 to USD 77.57. The reason for this is believed to be lower demand given a weaker global economy.

The Eastern Africa region is facing drought leading to famine conditions that is not helping. Severe shortages of basic commodities due to adverse climatic conditions and reduced availability of imported commodities, is going to plague regional Governments in 2023. Ongoing conflicts are not helping either as what little aid is available cannot safely reach the people most affected.

|

“The global economy is projected to grow by 1.7% in 2023 and 2.7% in 2024. The sharp downturn in growth is expected to be widespread, with forecasts in 2023 revised down for 95% of advanced economies and nearly 70% of emerging market and developing economies”. World Bank Global Economic Prospects |

Macroeconomic stability

The Economist predicts: “The world economy is slowing and many countries risk falling into recession in 2023” as the world moves into a period of “high inflation and economic stagnation”. The high profit margins that many Western economies experienced in 2022 came from strong consumer demand coming on the back of depressed spending during the peak of the pandemic. Unfortunately, with inflationary pressures, this year is unlikely to be as forgiving. Reduced consumer demand because of high inflation is going to put pressure on business, which might likely be a global phenomenon. With the US hiking interest rates, the US dollar has strengthened globally resulting in increased costs and significant inflationary pressure elsewhere. One country that is believed will buck global trends is India, which by all accounts is booming!

For business to deal with this, their thinking and strategies will have to change which may be difficult given the last time the world was in this condition was probably the 1970s! Inevitably there will be the usual attempt to pass the increases on to customers but even this will not work indefinitely as consumers struggle to make ends meet themselves. According to the Economist, businesses with “strong pricing power” either because they sell essentials that the consumer cannot do without or their brand is one that is deemed to be trusted, one such example being Coca Cola.

Those that do not have the pricing power will need other strategies. These could include selling less quantity at the same price, introducing cost efficiencies or even moving production to other locations. But the most difficult issue facing them will be wages that cannot be decreased and pay rises that cannot be given despite the demands from unions. Potentially, this could mean lay-offs but unfortunately, Government support such as the UK’s Covid furlough scheme, will not be there to cushion workers. Any business that successfully manages to adopt new and innovative strategies will undoubtedly come out of 2023 better than they went in!

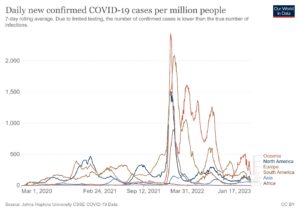

In the Eastern Africa region, increased Government debt particularly during 2020 and 2021, will be a concern for macroeconomic stability. Servicing the high level of debt in an environment where tax revenues will not be as robust and aid and other funding more difficult to obtain, is going to be challenging. The current drought conditions in many parts of the region are a further obstacle for Governments to tackle.

2023 – make or break?

It certainly seems that 2023 will be a tough year globally and in the Eastern Africa region. Both the public and private sector will need to have innovative strategies to cope with the difficult environment we find ourselves in. Human kind, however, is nothing if not resilient and while it may be tough, we must not let 2023 break us!